Inside Ugly Sister’s 214 mph 650 ci Big-Block Chevy

May 2020 • By Nick Davies, ICEAutomotive.co.uk

Photography courtesy Matt Woods, Nick Davies and Tony ThackerAndy Bond, owner of the ‘Ugly Sister’ ’56 Chevy and I are old friends, he used to crew on my Pro Mod Olds Cutlass. For a while he ran a 600 ci Street Eliminator Mustang Cobra with nitrous. Unfortunately, it was only tagged to 8.50 and was uncompetitive. Andy wanted to go faster and talked to Rob and myself about ways to do it.

Nick Davies of ICEAutomotive.co.uk and Andy Bond owner of Ugly Sister have been friends since Andy crewed on Nick’s Pro Mod Olds Cutlass.

We have some pedigree in the drag racing turbo world. We built the engine for the first turbo Street Eliminator (SE) car around 2003 after helping other racers dominate the class with our previous nitrous configurations. During that process, a number of turbo ‘experts’ told us that we were crazy trying to turbocharge a 600 ci big-block Ford because everyone at the time was using small blocks. It was what the customer had so we intended to do it regardless. One exception to that group was turbo ‘guru’ Kenny Duttweiler who, whilst not telling us that it would work, certainly suggested that there was no reason not to give it a go. He turned into a good friend and the car, a steel ’68 Mercury Cougar, flew.

The Street Eliminator Mustang and Plymouth Superbird Pro Mod of Richard Billings and Alan Cook in the shop at ICEAutomotive.co.uk, Silverstone, England. Nick drove the Superbird for a year but eventually it was totaled.

In 2010 we were asked to build an engine for the UK’s first turbo Pro Mod car—the now totaled Plymouth Superbird. At the same time, Richard Billings and Alan Cook asked us to build another turbo SE engine for their Mustang alongside the Pro Mod car. We built both in our workshop and I ended up driving the Superbird for a year to help develop it. We, Mark Harrison from the HorsepowerFactoryuk.com who built and supplied the loom as well as bringing immeasurable value on the Motec electronics, and the cars owners, were somewhat ‘handcuffed’ as the chassis was only tagged to 7.50 and the car had much quicker ability. We therefore focused on trying to run as high a terminal speed as possible without going quicker than 7.50. The Mustang eventually ran just over 209mph.

We learned a lot on the Mustang in terms of configuration, materials, camshaft design, boost levels, static and dynamic compression that we were able to apply on Andy's build.

Andy’s ’56 Chevy had previously run a Sonny’s big-block hemi-headed Chevy with nitrous but we all agreed that the turbo route was the way forward. Nitrous is great but the SE class had evolved and the rulebook encouraged us down the turbo path. This time, with the benefit of time being on our side, a sensible budget and a chassis that was tagged to 6.00, we were able to choose the configuration we thought best suited to the class.

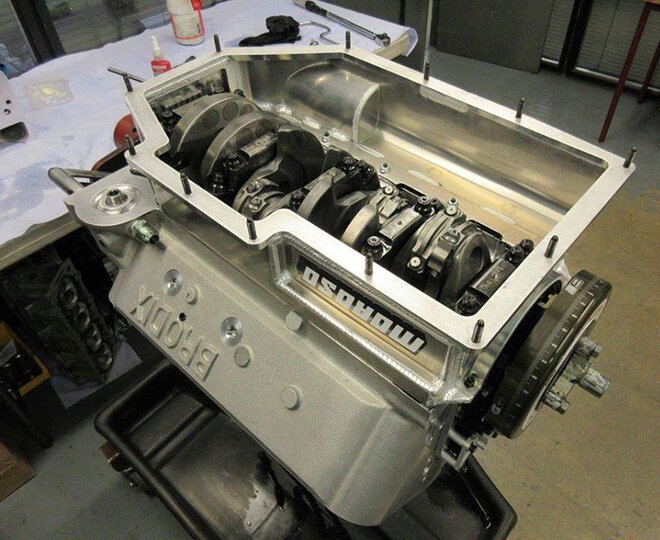

Having worked with their products over the years, we elected to start with one of Brodix’s 5-inch bore center blocks and calculated that around 650 ci would put us safely inside the maximum load recommendation on the strongest commonly available rod bolts that we could find. Experience has taught us the hard work is done at the spec stage and building the engine is then relatively straightforward.

Increasing the bore centers from a standard 4.84 inches to 5.00 inches imparts greater strength, better sealing andw flexibility for larger bore sizes and therefore bigger valves. Setting the maximum boost and rod ratio we ended up being able to run a bore size of 4.68 inches which would not have been, in our view, practical with a standard bore spacing.

We always treat the bottom-end as our insurance policy and encourage customers to invest what they can as premium quality components will always pay dividends. Here, the Bryant crank and Oliver rods can be seen in a trial assembly.

A split oil pan was chosen to allow ease of access for checking bearing condition quickly and cleanly. End-rail seals on a Chevy pan can be a little tricky upside down and with the clock ticking, a split pan all but eliminates this issue.

Brodix’s 5.0 cylinder heads are a perfect match for their spread bore center blocks. Although not a volume selling product, Brodix have put in the development to offer the complete package for their 5.0 range from blocks through heads and valve covers.

Chambers are hand-finished in-house, specific to customer application flowbench testing. We favor the soft chamber design and modify the quench area to reduce the knock susceptibility in many turbo, blown and nitrous applications.

Copper seats, bronze intake guides and custom ICEAutomotive.co.uk turbo exhaust guides. We make our own guides in-house and send them to Brodix for fitting.

We have used Jesel valve train parts where possible in the majority of recent builds. Their range and quality are exceptional. Here we use their rockers and belt drive system. Note the cam sync pickup for the engine management on the drive gear.

Detonation can be fatal with these engines. If present, the earlier it can be detected and eliminated the better. Here, we built an internal loom for early ‘knock’-sensing. Sensitivity is increased closer to the source of detonation so, by putting the sensor in the valley, we tried to get as close to any potential source as possible.

Although it presents packaging and cost disadvantages, dry-sump oiling allows huge flexibility particularly around the scavenge systems. We run a multi-stage system allowing oil to be returned quickly to the tank from the heads, turbos and pan.

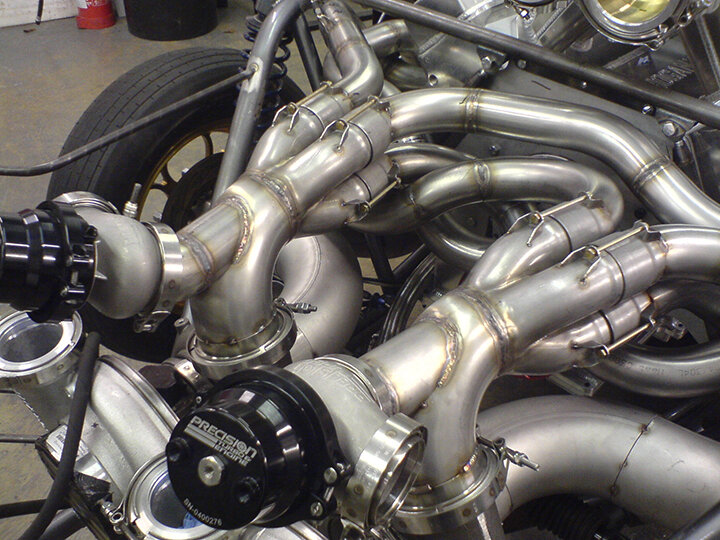

Our dyno doesn’t allow for full-power testing with the 89 mm Precision turbos so we break the engine in and straighten the fueling out normally aspirated. The engine is then installed with the turbos and it goes onto a chassis dyno for further mapping.

Made-to-measure. Once installed, the HorsepowerFactoryuk.com loom could be installed and an initial boosted engine map, based on the information learned from the Mustang, was installed in the new Motec M1 system.

Ugly’s engine has scarcely missed a beat since installation and valve covers rarely come off. It has switchable E85 and Unleaded gas maps and nothing else is changed when it switches from street to track—no tire change, no wheelie bars. It has a full-size cooling system and will happily sit in traffic with no issues. To date, it has run 6.92 at 214 and makes around 2,400hp. Targets achieved and mission accomplished.

If you want to see the finished car, go here.